Transforming a school is a long, hard, and often lonely task. Some people want change, others don’t, and some simply aren’t prepared to wait for results to show. As a school leader sets off on this journey, how do they know what to do, when to do it, who to listen to, and how to manage critics along the way?

Our study of the

actions and impact of 411 leaders of UK academies found that only 62 of them managed their turnaround successfully and sustainably transformed their school. While other leaders managed to create a school that looked good while they were there, but then went backwards, these 62 leaders built a school that continued to improve long after they’d left. We call them Architects, because they systematically redesign the school and transform the community it serves.

We studied them over eight years, using 64 investment and 24 performance variables to identify what they did, when they did it, and the impact they had. We visited the schools to see first-hand their actions and results. And we interviewed the leaders and their teams to understand the challenges they faced, when they occurred, and how they overcame them.

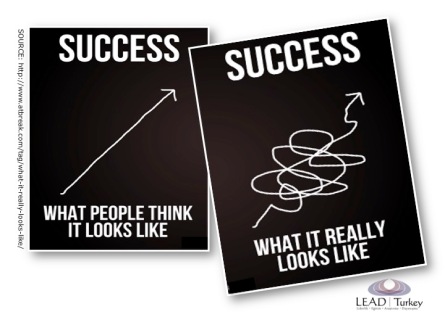

We found the Architects sustainably transformed a school by challenging how it operated, engaging its community, and improving its teaching. They took nine key steps over three years, in a particular order. Each step represented a different building block in the school performance pyramid. But it was a bumpy ride, with 90% almost fired at the end of their second year. Here’s what they did, and how they did it.

The school performance pyramid

Building Block 1—Challenge the system: stay for at least 5 years. The first step is to develop a 10-year plan, clearly showing how you aim to transform the school and the community it serves. This shows everyone you’re committed to the long haul — like your students and their families — and are prepared to make tough decisions and manage their consequences. As one Architect said, “No one trusts you at the beginning. They’ve been let down too many times by too many people. That’s why I moved to the local area — to show I was committed to the school, the community and to making it work. I wasn’t going to walk away halfway through, like the other Heads before me.” In our study, it took at least five years to engage a school’s community, change its culture and improve its teaching. The most successful leaders stayed for the whole of this journey, and often longer, with test scores increasing by an impressive 45-50 percentage points in the first eight years after they took over. This doubled, or even tripled, the number of students graduating with five or more grade Cs,

increasing their projected lifetime earnings by £140,000.

Building Block 2—Teach everyone: expel less than 3% of students. Once you’ve committed to the journey, then you need to commit to the community. You can’t just kick kids out to improve test scores. You need to show parents and students you want to help them. Show you want to fix the problem, not give it to someone else.

This doesn’t mean you can ignore poor behavior, be nice to everyone, and expect them to like you. But you should only expel students as a last resort — when everything else has failed. In our study, the most successful leaders suspended 10-15% students in the first three years after they arrived, but expelled less than 3%. As one Architect told us, “If you start kicking kids out as soon as you arrive, then your community wonders if you’re trying to help or get rid of them. Instead of expelling students and passing the problem to someone else, we created multiple pathways inside our school — so we could manage and improve behavior ourselves.”

Building Block 3—Teach for longer: from ages 5 to 18. Of all the changes made by the leaders in our study, teaching kids for longer was the one with the most consistent impact. It took five years to see results, but test scores then suddenly jumped by nine percentage points and continued to improve by five percentage points each year after that.

Teaching kids from a younger age meant the schools could embed the right behaviors earlier on, teach the kids in a consistent way for longer (for 13 years, rather than 5) and create valuable resources (as revenues increased by 30-40%). And teaching them up to age 18 gave the younger kids something to aim for. As another Architect explained, “Setting up a sixth form was one of the best things we did — even though it still loses money! Last year, 51% of our sixth formers went to university — compared with only 27% four years ago. This sends a great message to our younger students, and we use the older ones to mentor them as they progress through the school.” (In the UK, “

sixth form” is a final, sometimes optional phase of secondary education in which students prepare for college entry exams.)

Building block 4—Challenge the staff: change 30-50%. Now it’s time to start changing how the school works. That usually means changing staff. “Too many Heads duck the issue of firing poor teachers,” one Architect told us. “But you have to ask yourself: who are you here to help — the students or the teachers? I believe you let down 30 students a year by protecting one incompetent teacher. Once you start thinking like that, the tough decisions become easier to take.”

In our study, the most successful leaders changed 30-50% of staff in the first 3 years by clarifying teaching and marking targets, displaying real-time performance (such as attendance, behavior and test scores) on video screens in corridors and staff rooms, and managing out poor performers. Typically, a half of this change came from recruiting new staff to resource growth, a quarter from reducing the number of supply teachers and a quarter from managing out poor performers. Leaders who changed less than 30% of staff had little impact, while more than 50% created too much disruption. As another Architect told us, “The culture in the school suddenly tipped when we had 30% new staff, people who were serious about trying to transform the school and the community it serves.”

Building block 5 — Engage students: keep 95% in class. It’s pretty simple really. You can’t teach your kids if they’re not there — or don’t care. However, it’s easier said than done. As one Architect explained, “Half our students live in poverty, in communities that have been let down by their schools for generations. That’s their starting point, so you can see why they’re not interested. But, after two years of hard work, things suddenly started to change. They started believing in themselves – and that we could help them. Instead of saying ‘there’s no point’ or ‘I can’t be bothered’, they’re now saying ‘I aced that test’ or ‘I’m going to be a doctor’.”

The turning point in the schools we studied occurred when at least 95% students attended all their classes. And the most successful leaders achieved this in the first 3 years—by bringing in external speakers to inspire students, asking students to evaluate teachers, so they felt part of the process, and getting older students mentor the younger ones, so they had someone to look up to.

Building Block 6 — Challenge the board: manage 30-60% of them. It doesn’t matter what your governors say, they all want test scores to improve as quickly as possible. (In the UK system, “governors” are the school’s board of directors.) They’ll give you one year’s grace, but then they want some hard evidence that the school is improving. If you can’t do this, then you’re often out of a job. But the most effective, most sustainable actions take three years to show results. So, how can you show you’re on the right track when test scores are still the same?

In our study, the best early signs of sustained improvement were teaching students from ages 5 to 18, having 95% of students in class, 50% of parents at parents’ evenings and 70% of staff with no absence. Leaders who achieved all this in the first three years subsequently improved test scores by 45-50% in the following six years. However, 90% of them were almost fired at the end of the second year, as test scores hadn’t improved fast enough. They survived this challenge by moving the discussion away from this year’s test scores to the progression of students aged 11 to 13.

Architect leaders can also emphasize other metrics, such as more students attending classes, more parents coming to parents’ evenings, and fewer staff member absences. As one Architect told us, “Too many boards simply fire their Heads when there’s a problem. Instead, they need to make sure the Head is around long enough to have an impact and help them make the right decisions along the way.” A strong, healthy board was critical to the success of all the schools in our study, with the best leaders challenged by 30-60% of governors on key decisions in their first three years. Poor decisions were made if the challenge was less than 30%, and the leader lost control of the school if the challenge was greater than 60%.

It’s important to take time to get to know your governors, build relationships with them and understand their needs—so they trust you and understand why you’re not focusing on this year’s test scores. Their concerns are legitimate and need to be managed. Use their challenge to help improve decision making—to better explain why decisions are made and the impact they’ll have.

Building Block 7 — Engage parents: have 50% at parents’ evenings. You need to start engaging your parents right from the start, but it can take a while to happen. This is particularly true in

rural or coastal schools in the UK, where people are less mobile and parents and grandparents may have attended the same school. As one Architect explained, “Our parents and grandparents had very strong views about the school based on what it did for them. It took a long time to change these views. But, if we hadn’t, then all our hard work would have disappeared when our students went home.”

Attendance at parents’ night was as low as 10% when many leaders first arrived — but the most successful ones increased it to more than 50% by the end of the third year. They did this by making it a social event with food, drink, and student performances, offering education and support services such as IT skills and career advice, and providing similar services at home through outreach programs.

Building block 8 — Engage staff: 70% with no absence. Engaging your staff also takes time. “You walk into a very stressful environment,” one Architect explained. “Your staff have just been told they’ve failed and you’re here to sort them out. You need to convince them that you’re here to help. That their jobs will get easier and become more fulfilling if they work with you, rather than against you. In the year before I took over, we had 14 staff on long-term sick leave and only 20% of staff with no absence. Now it’s up at 90% — that’s a big shift in three years!”

In our study, the most successful schools had more than 70% staff with no absence by the end of the third year. They did this by reducing the number of supply teachers, asking teachers to evaluate each other (through informal observations), team teaching, visiting other schools (to see how they worked) and simplifying processes to reduce administration and paperwork.

Building Block 9 — Teach better: 100% capable staff. Anyone can fire staff. The real question is: How do you replace them? “Good teachers don’t apply to work in failing schools in deprived areas,” one Architect told us. “They want to work in good schools with engaged students. So we contacted the good schools near us who’d recently advertised jobs and had more applicants than places. We asked them who else they’d employ, if they could. We then contacted these teachers and asked them to join us! We got some of our best teachers this way. Teachers who didn’t apply to work with us, but love being part of what we’re doing.” The most successful schools in our study all had 100% capable staff by the end of the third year. They achieved this by recruiting capable teachers, increasing informal teaching observations (through mentoring programs within and across subjects), and sharing best practices within and across schools. As another Architect said, “Too many poor teachers are simply moved from one school to another. We need to develop them, rather than simply passing them on to someone else.”

Building the pyramid in practice

Pick six building blocks out of nine: the 90/60 principle. We found it wasn’t always possible to put all nine building blocks in place in the first three years, no matter how hard you try. Sometimes, the board won’t support you, parents won’t engage with you, or you can’t find the right teachers. The good news is our research clearly shows there’s a tipping point in each transformation when six of the building blocks are in place — not all nine. The last three blocks help to sustain the transformation, but there are diminishing returns. Leaders who put all nine blocks in place in three years increased test scores by 50 percentage points in the following five years. But leaders who put in six blocks increased results by 45 percentage points. In other words, test scores increased by seven percentage points for each of the first six blocks put in place, but only by one percentage point for the three after that.

So, ask yourself: which are the six easiest, or most urgent, blocks to put in place first? And which can wait until later? If you can’t engage parents, then engage students. If you can’t engage students, then teach the ones you can, better and for longer. Find the right pattern of actions for your school; see the pyramid as a menu, rather than a recipe. Select, mix, and match the ingredients that work best for you.

Take your time. School leaders are often under huge pressure to turn the school around quickly, but sustainable transformation takes time. In our study, the schools that improved the most in the long term didn’t see test score improvements until year three, and continued to get better through year five and beyond. You need to explain this to your board, so you don’t get fired along the way. Fast improvements can only be achieved by expelling poor performing students or attracting better ones from other schools. And neither solution benefits the community in the long run. Instead, try to put 6 of the 9 blocks in place in the first three years. But, don’t worry if it takes longer — the improvement won’t be as fast, but it will happen. And it will be sustainable.

No single action or combination of actions is more significant than any other. Eighty percent of the best leaders stayed at the school for more than five years – but not all of them. And all the best schools taught kids from ages 5 to 18 – but so did 40% of the poor ones. Rather than searching for a silver bullet, put as many blocks in place as you can. Remember, the number is more important than the type.