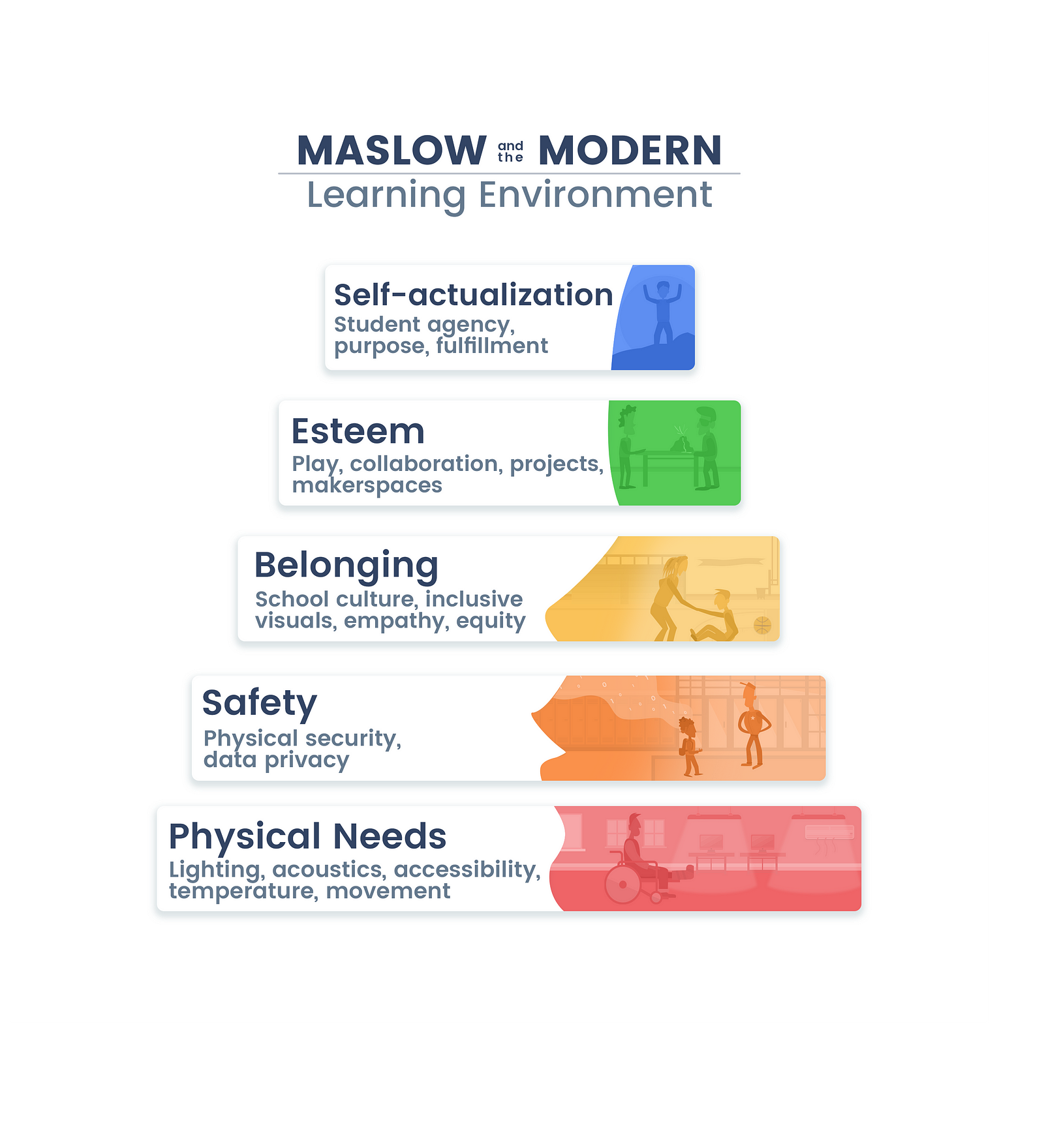

Maslow and the Modern Learning Environment

Editor’s note: A version of this article was originally published on eSchool News 6/19/18.

What can we learn from human psychology about designing learning environments geared for maximum motivation?

Let’s start by identifying core human motivations using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs. Psychologist Abraham Maslow studied human motivation as a whole, rather than the discrete pockets of motivation prior studies had identified. Maslow’s Hierarchy is depicted as a pyramid, with the base of the structure housing the most basic needs and more rigorous needs building on top of those. Maslow referred to the first four levels of the hierarchy as deficiency needs, which is to say each lower-level need should be met before proceeding to the next level. Should any lower-level need become deficient in the future, people will work to correct the deficiency before moving forward.

All this motivation builds toward the tip of the pyramid: self-actualization. This may seem like a stretch for students, given that most adults spend their lives striving toward this lofty goal. When we build a safe, motivating place for students to turn their focus inward, they’re free to pursue the beginning of self-actualization. How’s that for whole-child education?

So how exactly do school leaders create a learning environment geared toward nurturing and motivating the whole child? Let’s take a cue from Maslow and start at the base of the Hierarchy of Human Needs.

Physical Needs

The most fundamental human needs linked to bodily comfort and function make up the wide base of the pyramid. In a school setting, we can equate this to creating an accessible, functional environment for all students. A group effort is required to achieve this in schools and districts — enlist the help of the school business office and maintenance teams to correct deficiencies where you find them.

Sources of light in classrooms — whether natural, fluorescent, or some combination of alternative lighting — must be bright enough for students to complete their work. If possible, place SMART boards or other demonstration locations away from any glare from windows or lights.

Help students focus with appropriate sound levels during lessons. To change the acoustics (how sound travels) throughout the learning environment, place textiles and upholstered items strategically to minimize sound absorption near demonstration areas, and increase absorption near echoey cinderblock walls. Consider playing some light background music during group activities to help students focus on the voices nearest to them. For some students, acoustics of a classroom are the difference between receiving a high-quality education and straining to catch snippets of instruction all day.

Accessibility isn’t a trend in learning environments — it’s the law. Follow the basic ADA checklist for existing facilities to ensure accessibility for all students.

Inspect and maintain HVAC systems to ensure a comfortable temperature for learning. Heating problems resulted in frigid temps and burst pipes in Baltimore Public Schools, ultimately shuttering the district over winter 2017.

Finally, movement is a key component of modern learning environments. One method of freeing up space in classrooms is the über-trendy flexible seating strategy. Contrary to popular belief, flex seating is a solution to large class sizes (desks take up tons of precious space!) and it doesn’t have to cost a lot to add a few great options. Sara Moser, head teacher at Benjamin Chambers Elementary in Pennsylvania, added Adirondack beach chairs she and her husband made for flexible seating in her third-grade classroom.

“They’re super big,” she says. “Kids can put their feet up, lay on it, sit on the floor and use it as a desk; it all depends on the kid.”

There are thousands of resources on this topic (like the Classroom Eye Candy series). The goal is to embrace movement as you break out of the cemetery rows. Promote seat rotation by requesting students choose a new place to sit every few days or weeks.

Safety

Once students’ physical needs are met, turn your focus toward keeping people out of danger — in classrooms and well beyond. Physical safety is everyone’s responsibility every day at school. Challenge staff to look at your environment with fresh eyes every day to spot and speak up about risks before they become hazards.

Students’ digital safety is important in school as well. Data privacy laws, including FERPA, protect their personal information and school records. Digital safety extends beyond student records and information controlled in your main office. Does your district have a recovery plan in the event of a disaster or security breach? What will you do if your data is ransomed? The key component to a speedy recovery is having a proactive plan in place in the event of a data breach.

Belonging

The next tier of motivation relates to the human need to feel an affiliation and be accepted by others. When students feel like they belong, they are able to show vulnerability, take risks, and try new things to stretch the boundaries of creativity. Igniting this deep feeling demands more than simply telling kids they belong — they have to feel they’re part of a close-knit group.

In Daniel Coyle’s book The Culture Code, he explores the characteristics of outstanding cultures in businesses and teams, including the presence of belonging cues. These cues send a powerful message to the subconscious brain, “Here is a safe place to give effort.”

Focus on cultivating a welcoming school culture. This takes patience, commitment, and time, but the effects are far-reaching — districts with a strong school culture become destinations for high-performing, dedicated employees, and the benefits snowball from there.

Research tells us incorporating visual representation of all types of students is important. Head teacher Sara Moser enlists her third graders’ help with decorating their classroom.

“I don’t put up a lot at the beginning of the year. Everything in the room is authentic,” she explains. “Either I created it, my husband built it, or the students have made it.”

“I don’t put up a lot at the beginning of the year. Everything in the room is authentic,” she explains. “Either I created it, my husband built it, or the students have made it.”

Educating and motivating the whole child incorporates academic skills alongside life skills, including social-emotional learning. Modelling empathy at all levels of leadership in your district helps create a positive, encouraging, and energized culture geared toward growth.

Finally, as much as possible, create a learning environment built on equity for students and teachers. First, identify and remove obstacles holding subgroups of students back from reaching their full potential — a key concept of many states’ approved ESSA plans. Next, listen to students’ feedback on classroom topics. When appropriate, incorporate their thoughts into your lesson plans to increase ownership and motivation.

Esteem

Once students’ physical needs are met, they are out of danger, and feel they belong, their next motivator is the need for esteem. This tier represents the need to achieve, be competent, and gain recognition or approval from peers and teachers.

Play-based activity for early learners sets the stage for esteem needs. In a drastic shift away from the “kindergarten is the new first grade” trend, schools are incorporating learning models used in preschools. Early learning educators are toning down the structure and encouraging developmentally appropriate student-led activities and choices. One kindergarten teacher told NPR she has noticed improvement in students’ oral-language development and critical thinking skills. Researchers are studying the far-reaching effects of this approach.

Encourage collaboration in learning environments by identifying specific space for whole group, small groups, pairs, and even for individual reflection (maybe tucked away in a corner). If your school is open to it, consider making use of the hallways fair game. Large scale science or math experiments, quiet pair work, or individual reflection can all take place in hallway collaboration space.

For older students, build esteem by incorporating project-based learning. High quality project-based learning not only prepares students for the highly innovative careers on the horizon, but also spikes motivation when projects align to their unique passions. Along similar lines, makerspaces geared toward self-directed STEM exploration also encourage design thinking, engineering, coding, and other creative learning. It’s possible to build a great makerspace on the cheap — most important is a safe, lightly supervised space where kids can test the boundaries of their best ideas to see if they can make them a reality using their own two hands. (And probably a lot of hot glue.)

Self-Actualization

When learning environments fulfill students’ deficiency needs, they’re equipped to shift their motivation and focus inward, toward what Maslow called growth needs or the pursuit of self-actualization. This isn’t a destination, but rather a life-long journey to realize their own potential and become self-fulfilled, then identify ways they can help others along the way (Maslow called this self-transcendence).

At this very tip-top of the Hierarchy of Human Needs, motivation comes from within. Students respond to intrinsic motivation, giving effort to tasks at hand purely because it is gratifying to them. In a learning environment, this corresponds to student agency — shifting students’ mindsets, encouraging them to choose their learning paths, and sharing ownership of their education. This profile of the Chrome Squad, the student-led IT team at Royse City High School in Texas, tells the story of student agency in action and shares its results: students who gain accountability, problem solving, and service skills they’ll use and take pride in for the rest of their lives.

Creating a highly motivating learning environment takes real dedication and more than a little elbow grease. The payoff comes when teaching and learning takes off in ways that shape the whole child (and every child) for life. Take these cues from universal human needs to build a strong, safe foundation for students to take risks and get to know who they are, and who they’re becoming.